What is a meniscus and what does it do?

A meniscus is a protective disc positioned between bones which serves to absorb and disperse force. The menisci we hear about most often are those in the knee. The knee menisci can be damaged in isolation or in conjunction with other knee injuries, e.g. an ACL tear. A meniscal injury can cause a range of problems which may include:

- Swelling

- Clicking

- Catching when you attempt to straighten the knee

- A sense that your leg is about to give way

If you or your client are experiencing this sort of problem, it is best if this is assessed by a doctor or physiotherapist before proceeding with any exercise programs.

In this article we review:

- The anatomy of the knee and the meniscus

- Examples of protocols for meniscus injury repair

- Exercises and some considerations in a movement studio

A review of the anatomy of the meniscus of the knee

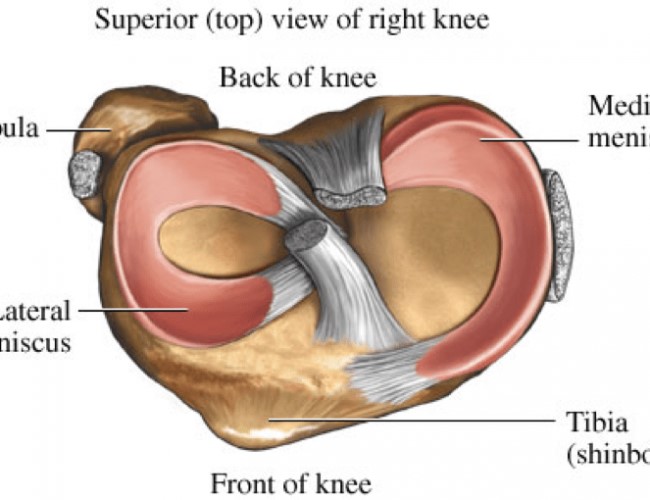

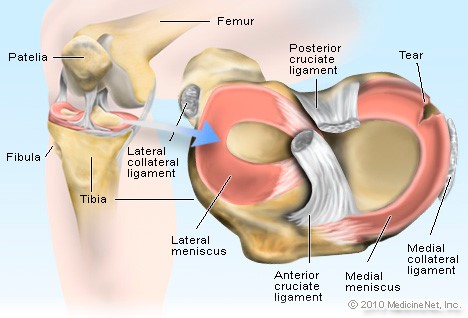

There are two menisci in each knee joint. They are crescent-shaped lamellae (think a croissant), each with an anterior and posterior horn.

The menisci:

- Improve weight distribution and shock absorption of the tibia (which is the the bone that forms the bottom part of the knee joint)

- Help to guide and coordinate knee motion, making them very important stabilisers of the knee

- Disperse compressive loads so that the hyaline articular cartilage of the knee is not damaged. This is essential as the compressive loads through the knee can reach 1-2 times body weight during gait and stair climbing and an astonishing 3-4 times body weight during running. This is why being overweight can contribute to problems within the knee joint.

The medial and the lateral menisci have different shapes, structures and roles. Accordingly, lateral and medial menisci injuries can differ.

When you look at the image of the meniscus you can see:

- The medial meniscus appears “C” shaped. The horns (pointy end bits) are further apart. The medial meniscus bears more of the compressive load from the femur bone and is more prone to damage.

- The lateral meniscus appears more ‘O’ shaped and is more mobile than the medial meniscus, as it is attached to the fibrous capsule that protects the knee. The mobility of the lateral meniscus means that it is able to move with the knee and is less likely to be damaged.

It is important to note that the location of the menisci in the knee mean that they have little blood supply to help with healing when they are injured. It is also important to remember that people can have a meniscus injury and experience no pain or problems until many years later when that meniscus has been worn away.

How is the meniscus damaged?

An acute meniscal injury often occurs in activities that involve rapid twisting, rotating and changes of direction e.g. skateboarding, netball and skiing. Anyone can damage their meniscus, however older women may be susceptible to injuries to the menisci as the angle of their hips are such that it places more force on the medial aspect (inside).

What is a bucket handle tear of the meniscus?

A bucket handle tear type of injury to the meniscus normally requires surgery. In the video below physiotherapist Lachlan Loose is explaining what a bucket handle tear is and how it affects your movement.

What can you do to help recover from a meniscus injury?

A physiotherapist or doctor is needed for accurate diagnosis, as a meniscal injury may present similarly to other structural injuries to the knee.

Meniscal injuries can be acute or chronic (degenerative). Injuries are often classified by:

- The length

- The depth

- The tear pattern

Once a meniscal injury has been identified, the next step is rehabilitation. Exercise therapy and knee arthroscopy (a common surgical approach) can be similarly effective for pain relief. Exercise therapy resulted in better thigh muscle strength than surgery (Kise et al., 2016) .

Supervised exercises should be considered as a treatment option for patients with pain and degenerative meniscal tears verified by magnetic resonance imaging and without radiographic signs of osteoarthritis.

What this means is that surgery is not always indicated for an injured meniscus

A physiotherapist will facilitate appropriate selection of exercises that will be effective for pain relief, muscle strength and ideally returning to your pre-injured state. There are different protocols for meniscus repair including the conventional, accelerated and individualised rehabilitation protocols. The specifics of these can vary depending on the specifics of your particular injury and your individual presentation and progression. Below are some examples of what you could potentially see.

A conventional (non surgical) rehabilitation protocol:

- No weight bearing during the first 3-4 weeks

- Quadriceps and hamstring strengthening exercises begin by 2-3 weeks

- Cycling is allowed after 2 months

- Running is allowed only after 5-6 months

The accelerated and individualised rehabilitation protocol could be applied to an athlete who needs to return to high level activity, or perhaps those people who can access intensive physiotherapy (3 times a week) and focused Pilates classes. This strategy requires high monitoring so that re-injury does not occur. In this scenario there may be:

- Weight bearing immediately after the meniscal repair

- Movement limited to no more than 90° of flexion during the first 6 weeks, and possibly longer depending on a surgeon’s protocols or the severity of the injury

- If there is an anterior horn meniscus repair, hyperextension should be avoided during the healing process, i.e. about 4-5 months

- Cycling and swimming may be allowed 6 weeks after surgery

- Full flexion and extension may be allowed after 4-5 months

Other than the type of repair, other considerations for meniscal injury are the duration of the injury. Long standing meniscal tears may have led to compensatory patterns and muscle adaptations at the hip, ankle and opposite side and these should be addressed.

What exercises for a meniscus injury and recovery?

Exercise examples in a Pilates or Gyrotonic studio:

- Care with introduction of knee flexion, remember not to take the knee beyond 90 degrees of flexion for the first 6-12 weeks after injury, or as the surgeon recommends. During this stage:

- Knee extensions first with a ball or rolled up towel under the knee and hold for up to 30 seconds

- Progress to be able to sit and hold the leg out straight for up to 30 seconds without compression

- When progressing knee flexion, start the person with double legs for example foot work on the reformer and then slowly progress to single leg work on flexion, e.g. be careful about adding scooter in too early. Perhaps use a CoreAlign series of exercises first, for example hoof. I like to do leg slides. In the photo I have Max standing with the Makarlu under his foot to help him activate the intrinsic muscles of his foot. Also placement under the medial longitudinal arch is helpful to help with medial menisci damage so that the tibia (remember menisci sit on this) can be aligned more appropriately.

For those with a Gyrotonic tower, the seated leg series is fantastic for this. I put the Makarlu under the foot as well, to help with sensory awakening and also muscle activation. I would focus on front and back forward and as usual be very focused on the circle aspect of the exercise making sure the movement is coming from the hips not the knee. The Gyrotoner is fantastic for this.

For those with a Gyrotonic tower, the seated leg series is fantastic for this. I put the Makarlu under the foot as well, to help with sensory awakening and also muscle activation. I would focus on front and back forward and as usual be very focused on the circle aspect of the exercise making sure the movement is coming from the hips not the knee. The Gyrotoner is fantastic for this.

- Make sure the person does not work to a pain level beyond 5 out of 10. Also be aware that a person should not have pain or a flaring of pain above a 5 level for more than 24 hours after a session. If the pain levels are happening in these ranges then a return visit to their doctor or physiotherapist maybe needed for further investigations.

- Bridging with considerations for foot placement in order to decrease compressive load in the knee. In this example Lachlan’s knee is too flexed and we would move his leg away from the body and then progressively move it in over a period of 3-4 months.Again I have used the Makarlu hardwood timber base here to help with alignment of the foot and strengthen intrinsic muscles of the foot. Lachlan is also having a glute release here as he has probably been limping for a while and as a result tightened up in the hips. The glute release using the Makarlu is helpful.

- Modification to Leg series – decreased resistance, change of foot bar angle. Lower, the foot bar if you can to reduce the compression of the knee joint.

- Use of straps and springs in order to lightly traction the joint such as on the trapeze table. We would continue to do this work in weekly sessions as the process would help create the needed space in the joints before the person starts loading the joint, in other words it will facilitate alignment.

- Leg press on the Wunda chair seated or standing depending on level of rehabilitation and injury site and condition. Use the Makarlu for leg support.

- Standing leg curl in the reformer well – loading the injured leg in single leg stance or for hamstring strength on the moving side.

- Exercises like Scooter would work well around the 8-12 week mark, but once again I would give the person some support initially on the standing side. I would use the domes of the Makarlu or hedgehogs to support their feet and lower limb in alignment. It will help the person better recruit glutes.In a gyrotonic setting this is nicely achieved on the Jump Stretch Board. I particularly like doing this with the tracks on an incline as it helps the angle of the knee joint.

This is also nicely achieved through hoof or scooter on the CoreAlign.

- Ramp series work on the CoreAlign. This is nice to do starting seated at the end of the CoreAlign and progressing to standing.

Link to the complete article by Carla Mullins: Meniscus Injury of the Knee

Carla Mullins is co-director and co-owner of Body Organics, a multidisciplinary health and body movement practice with 3 studios in Brisbane. Carla is a Level 4 Professional Practitioner with the APMA and has also studied pilates with APMA, PITC as well as Polestar. She also has a LLB (QUT), M. Soc Sc & Policy (UNSW), Advanced Diploma of Pilates Movement Therapy (APMA), Diploma of Pilates Movement Therapy (APMA), Diploma Pilates Professional Practice (PITC), Gyrotonic Level 1, Gyrotonic JSB, Gyrotoner, CoreAlign Level 1, 2 and 3 and Certificate IV in Training and Assessment. Carla also has returned to University to complete an Occupational Therapy Degree.

References

BMJ 2016;354:i3740 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3740 Barber FA, McGarry JE (2007) Meniscal repair techniques. Sports Med

Arthrosc Rev Jokl P, Stull PA, Lynch JK et al (1989) Independent home versus supervised rehabilitation following arthroscopic knee surgery: a prospective randomized trial. Arthroscopy 5:298–305

Mariani PP, Santori N, Adriani E et al (1996) Accelerated rehabilitation after arthroscopic meniscal repair: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. Arthroscopy 12:680–688

Shelbourne KD, Patel DV, Adsit WS et al (1996) Rehabilitation after meniscal repair. Clin Sports Med 15:595–612

Comments are closed.