Many of my clients find it difficult to isolate movement of the hip from movement of the pelvis and lumbar spine, seemingly due to a range of imbalances in the hip musculature. I have often associated loss of hip isolation with the ‘elderly’, where anterior pelvic tilt and insufficient hip extension can lead to a marked shortening of stride length, predisposing them to poor balance and falls. Nowadays, I am seeing hip isolation issues more and more in the general population. Watch your clients walk and you may find that many of them also exhibit insufficient hip extension in the swing phase of gait, resulting in poor push off from the back foot in the toe off phase. Many also have poor stabilisation in the stance phase and exhibit a mild hip hike or even a Trendelenburg sign. (This is often more pronounced in stair climbing.) Now imagine the array of compensations this is leading to up and down the body. These clients may not be unstable or hesitant in their movement like our older friends, but neither are they striding through life in muscular harmony and balance!

Tightness and imbalance in the hips is often due to excessive sitting at work, driving etc. It can also be traced back to postural instability, with weak abdominals and over activity of the erector spinae leading to hyperactivity of the iliopsoas and anterior pelvic tilt. The gluteus maximus becomes inhibited and the hamstrings shorten to compensate (as described by Janda in his Lower Cross Syndrome).[1] Certain body types are also predisposed to weakness or tightness in the hips.

It is important to highlight that altered hip mechanics have ramifications for the entire lower kinetic chain and can also lead to altered pelvic and spinal mechanics.

Regardless of how the dysfunction begins, once the mechanics of the hip are altered, pelvic position is compromised and the individual has lost the postural alignment required for balanced abdominal activity, pelvic floor function and deep core stability. They are now caught in a downward spiral of compensations in the hip, leading to compensations in the pelvis and spine, which further compound the issues in the lower kinetic chain (hip, knee, ankle)… and on it goes.

The following are the key movement compensations that I see in the pelvis and lumbar spine, when a client has limited isolation of the hip joint:

- flexion of the hip is often accompanied with posterior pelvic tilt and lumbar kyphosis.

- hip extension is often accompanied with anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis.

- abduction and external rotation of the hip are often limited by short adductors, causing the pelvis to tilt or rotate

Kinetic chains and motor programs

Although difficulty in hip isolation is related to muscular imbalances, it is also connected to poor movement programs (CNS) and both must be addressed in any exercise program that seeks to improve the overall strength and stability of the body.

If one link (muscle or portion of muscle) is insufficient and/or weak, another muscle in the kinetic chain may be recruited to make up for the loss of stability or movement. If the muscle imbalance is not addressed…this may lead to persistent and fixed suboptimal motor programs in the CNS, chronic pain and/or poor performance. Frank, Kobesovar, Kolar. 2013.[2]

I have found that by the time a client seeks me out for Pilates to fix their hip (or their knee or ankle or even back!) these ‘sub-optimal’ patterns are already firmly established. Ultimately, I want these clients to be able to,

- isolate the movement of hip from rest of body, allowing for optimal movement in the trunk and pelvis and

- develop balance and support through the entire lower kinetic chain, from hip through to knee and ankle joint.

Fortunately, Pilates provides a comprehensive system of training that allows us to work on both at once, with the added benefit of the apparatus providing support and resistance in ideal alignment. In order to get the most from this system of neuromuscular exercise, we need to think in terms of a three-way interaction between (i) muscles, (ii) joints/bones and (iii) neurological function (CNS). The complete system of Pilates exercise provides us with the perfect templates to assess and correct these three elements and their interactions in a client’s movement patterns. Rather than training a client’s joint or muscle function in isolation, we can train it as part of a movement pattern. Rather than focusing on tight or weak muscles, we can focus on identifying the weak links in the kinetic chain. In these ways, we can train our client’s bodies AND brains in more functional movement programs.

Below are a few examples of basic system exercises I focus on to begin training my clients towards more functional and integrated hips. I have limited the examples to basic upright exercises performed on the sagittal plane, as neurologically these are the movements closest to those performed every day, by most people.

Enhancing Hip isolation within the Pilates system

The basic and intermediate systems of Pilates provide many hip isolation exercises in upright positions in different movement planes and at different levels of difficulty. These exercises can be used to both assess and teach key movement patterns in the hip and lower kinetic chain.

The neuromuscular benefits of using upright positions on the apparatus are:

- They help the client re-pattern everyday movements such as standing, sitting, squatting, walking, stair climbing and lunging. These movements can be in closed kinetic chain – which allows the development of joint stability, stimulates proprioception and enhances dynamic stability. They can also be a combination of open and closed kinetic chains, which can mimic and re-pattern the differentiated function of the limbs in gait.*

- They provide resistance in weight bearing, whilst offering support in ideal alignment. In most cases, the client is less likely to weight bear through badly aligned joints on the apparatus than they would be freestanding or in supine positions. Of course the more advanced the exercise the less support the apparatus provides, reminding us to make sure we choose the appropriate level of exercise not just for the clients strength, but for their coordination/neurological capacity.

*Please note – there is also great benefit in using pure open chain exercises, especially if we are focusing on a single joint for injury, or if a client has trouble weight bearing through the entire kinetic chain. These exercises are not the focus of this article.

Exercises in Closed Kinetic Chain (CKC) – moving the femur in the hip socket.

To simplify, let us look first at exercises where the kinetic change is closed and where there is no differentiation of the legs i.e. they are working symmetrically e.g. Elephant and Knee Stretches on the reformer. These exercises are a good starting place as they are the least neurologically challenging, the most stable and they also provide proprioceptive feedback via the apparatus. Throughout these exercises, we can not only observe and correct the relationship of the hip to the pelvis and spine, but also its relationship to the knee, ankle and foot (lower kinetic chain).

Ideally, in both the Elephant and Knee Stretches, the pelvis and spine remain stable in a relatively neutral alignment as the legs, initiating from the hip joint, move in and out underneath. The hips are working symmetrically in CKC through a range of flexion and extension. Because the feet are fixed, they act as an anchor for the muscles of the hip and thigh, allowing a caudal muscle pull in the kinetic chain from hip to ankle. This position, plus the resistance provided by the carriage and springs, allows the flexors and extensors to work in balanced eccentric/concentric co-contraction. Essentially, we are trying to train our clients to stabilise the spine and pelvis (meaning the hip sockets remain fixed) and allow the femurs to move unrestricted in the fixed sockets.

When teaching the exercise to a client for the first time, my teacher Romana would occasionally use a preparation for those clients who found the isolation difficult. Standing on the floor adjacent to the Reformer and flexing forward at the hip, she would have them hold the footbar with one hand to balance and then ask them to lift one foot just a little off the floor and swing the leg front and back, to feel the weight of the femur moving in the hip socket. Simplifying the movement to one leg and opening the kinetic chain helped the client feel the initiation of movement from the hip and also allowed them to recognise when they were hiking the hip.

Questions to ask:

- Is the movement isolated to the hip, or are the lumbar spine and pelvis involved? Is there posterior or anterior tilt of the pelvis, lumbar lordosis or kyphosis?

The answers and subsequent corrections will of course vary, according to a client’s postural type and muscle imbalances. Often if hamstrings are too short, lumbar spine kyphosis will appear; likewise short flexors can result in lumber lordosis or anterior pelvic tilt. Correcting or cueing the client into a more neutral position of the pelvis and spine will promote eccentric/concentric contraction of the hamstrings and flexors, allowing the hip to flex and extend without compensation in the lumbar spine. Sometimes we may need to cue the client to press into the heels to anchor the CKC and activate the caudal pull from the hip (both Elephant and Knee Stretches). If the client cannot perform the exercise without compensation in the pelvis, we may need to work on hamstring/hip flexor length in a less demanding position. If you do find it necessary to work on exercises with the goal of ‘stretching’ the restricted muscle group, remember it is important to always encourage correct alignment and dynamic co-contraction through the entire kinetic chain.

- Are they able to maintain neutral alignment in the hip, knee and ankle joints or is there excessive internal/external rotation? Do you see internal rotation at the hip? knock-knees, lack of dorsiflexion (heels rise), duck feet, excessive pronation/supination?

All of this information can be used not just to cue and improve the exercise at hand, but also to direct us to other exercises in the system that will help with the client’s specific issues. For example, the weakest link in the kinetic chain in the Elephant and Knee Stretches may be the inability to dorsiflex the ankle. We could then utilise the ‘Achilles stretch’ on the Electric or Wunda Chair, to develop muscle balance in the ankle and lower leg, again remembering to incorporate the isolated joint into the entire kinetic chain.

Differentiation – exercises that simulate gait

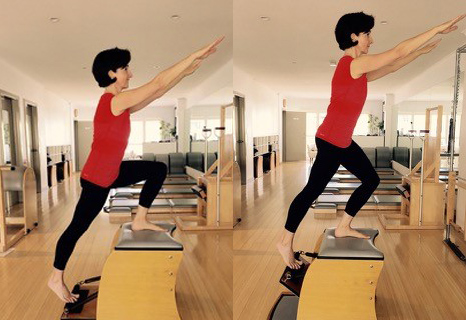

Crucial to improving hip isolation and thus function are exercises that simulate gait and the differentiated functions of the hips in this movement pattern. The balance control exercises on first the Electric Chair (Going up Front) and then on the Wunda Chair (Balance Control Front and Mountain Climb) are good gait re-patterning exercises as they involve a combination of open and closed chain movements.

Please note: If you do not have an Electric Chair, the exercises can be performed, to some extent, by placing your Wunda Chair next to a wall for support or using similar contemporary apparatus.

Going Up Front on the Electric Chair

Going up Front on the Electric Chair can improve hip extension in the back leg (swing phase), stabilisation of the spine and pelvis and finally, alignment and strengthening of the joints in the foot, ankle, knee and hip of the front leg (stance phase). It really is the complete package and if you have never tried it on an actual Electric Chair, I encourage you to do so!

Let us look first at the back leg extended behind, with the ball of the foot on the pedal and the ankle in plantar flexion (similar to the swing phase leg in gait). The leg is in an open kinetic chain and the springs are providing both resistance and support to the hip in extension. This position allows the iliopsoas to eccentrically contract caudally, towards the femur. Because the spine is upright (diagonally) and the diaphragm and pelvis in alignment, stabilisation of the torso will stabilise the origin of the iliopsoas at the thoracolumbar junction. All of these factors improve the client’s ability to perform isolated hip extension and can help reduce the compensations commonly seen in the pelvis and lumbar spine. (For example the tendency of the pelvis to anteriorly tilt as the hip extends, due to hyper tonicity of the iliopsoas.) The client can also use the arms for balance on the backboard, making it easier to keep the trunk upright, further enhancing alignment and core function. (As co-ordination improves, they can let go of the support and stretch the arms upward.)

Alternatively, the front leg is functioning as a fixed support/balance in a closed kinetic chain (similar to the stance phase leg in gait). There is flexion in all three joints, with the shin vertical and the thigh tracking in line with the 2nd toe. Ideally there is a neutral position in the joints of the hip, knee and ankle and the apparatus helps the client maintain this optimal alignment in weight bearing and movement. For example, the knee against the backboard and the foot on the seat, allows for approximation of the femoral head in the hip socket, correct tracking in the knee and dorsiflexion in the ankle. As the client moves, we can observe and correct the client’s alignment in the entire lower kinetic chain, as well as the relationship of the hip to the pelvis and spine.

If the client has a faulty movement pattern, the front hip will usually hike up and sway outwards as the client begins to extend the knee and hip in the upward movement. In these cases we can first cue the stabilisation of the trunk and pelvis to improve alignment and co-ordination. If the client is still unable to keep the hips level due to inhibition of the abductors, we can cue the lateral stabilisers and abductors of the hip in co-activation with the eccentric contraction of adductors. This will move the hip into a more neutral position and activate the appropriate muscle pathways.

This final correction brings us to a whole new set of imbalances – those between internal rotators/adductors and abductors. As mentioned in the introduction, these imbalances can also alter the alignment of the pelvis. Although we can identify and begin to address these imbalances in the basic system exercises above, we eventually need to bring the client into movements on the coronal plane, in order to train a balance of adductors, rotators and abductors.

Progressions

At an intermediate level we can see more movement of the hips in coronal plane. Examples include Side Splits on the reformer (closed chain and symmetrical function in the hips), Pumping Side on the Electric Chair and Balance Control Side on the Wunda Chair (differentiation of the hips with a combination of open and closed chain activities). All of these exercises require a balance of abductors/adductors and internal/external rotators of the hip.

Balnce Control Front on the Wunda Chair

When watching your client perform these exercises, the same questions can be asked as in the previous exercises and again what you see can be used to guide you in your exercise choices and cues for this client in the rest of the system. For example if a client is really struggling to open the hips in the Going up Side exercise on the Electric or Wunda Chair (Balance Control Front), we could work the balance of adductors and abductors in an open kinetic chain in the Hip Stretch on the Cadillac, maintaining all the principles of neuromuscular exercise discussed throughout the article.

A balance of body and mind – a neuromuscular focus

Pilates called his exercise a balance of body and mind and all his writings point towards a methodology for improving movement, not just building muscles or strengthening joints. I believe the more we can integrate neuromuscular thinking into our assessment and teaching, the more we are able to establish this elusive balance of body and mind. If we begin to think and cue in terms of movement patterns as opposed to isolated muscles or joints, our clients’ brains will follow our lead.

by Chris Lavelle

PAA Committee Member

[1] Page P, Frank C, Lardner R: Assessment & Treatment of Muscle Imbalances. The Janda Approach. Human Kinetics. 2010.

[2] Frank C, Kobesova A, Kolar P: Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilisation & Sports Rehabilitation, Int J Sports Phys Ther. , 2013 Feb;8(1): 62-73

Comments are closed.